These Prisoning Hills

On Southern Sci-Fi

By Darian Bianco

Growing up as an only child on my grandparents’ farmland, I was hungry for the impossible. I caught the bug early on, and any book called “unrealistic” was a book I wanted to get my hands on—give me mermaids, give me fairies, give me swords and robots and chosen one prophecies. I wanted it all.

Once I hit my tween years, my taste became a bit darker, perhaps a tad more bitter from all the coffee I was starting to drink; I wanted monsters, dystopia, darkness and uncertainty where people had to fight for the smallest sliver of hope.

Now, as a twenty-three-year-old, I can safely say that my taste has changed little if at all. I am still in love with magic, with futuristic science, with the leviathans of the unknown. Perhaps that love and hunger came from living in a place where my everyday was ordinary and safe. I looked out my windows to rolling hills, herds of cattle, the hard-working members of my family who smiled and shook their heads when I talked to the trees and cows in the backyard. I never thought that I could match my life to the stories I read, and the stories I made up. Farmland and creek beds didn’t go with wizards and AI. Kentucky wasn’t fantastical.

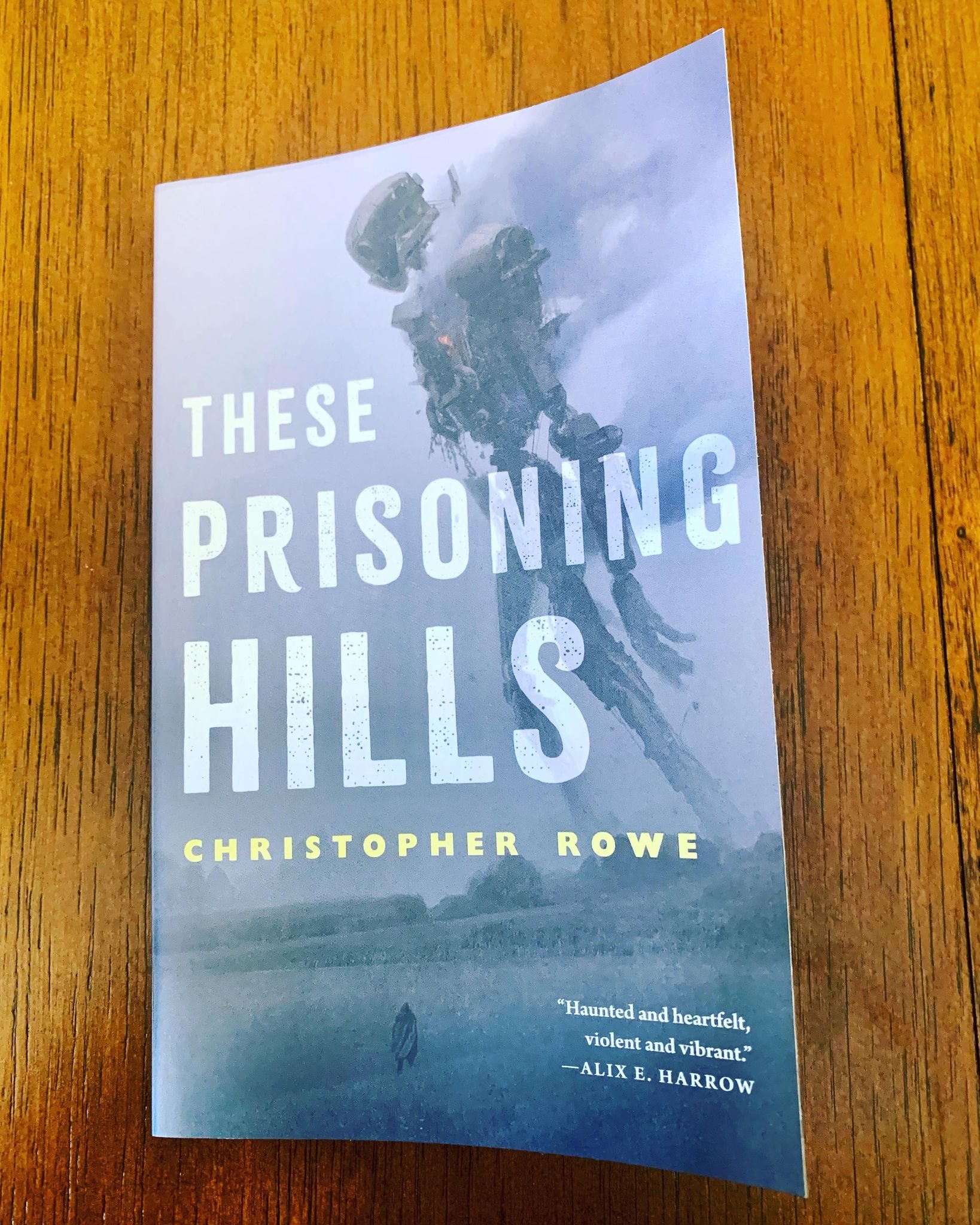

Enter: These Prisoning Hills by Christopher Rowe. This wasn’t the first book I read where the South and genre fiction came together, but it’s a book that has stuck with me, almost seeming to watch me from my bookshelf. The Commodore on the cover looms, an unthinkably huge mass of metal and smoke and fire, and in the foreground, we see a lone person, barely visible against the grey desolation. It looks like a story that takes place on an alien planet. Instead, it takes place in what I would call my backyard.

To give a brief synopsis without spoilers, These Prisoning Hills takes place in an already-established universe, where the Athena statue located in the Parthenon in Centennial Park, Nashville, Tennessee, has gained artificial intelligence and becomes the ruler of the Voluntary State of Tennessee. These Prisoning Hills comes after her war, after Athena Parthenus destroyed the American Southeast, contaminating the environment with nanotechnology and turning the land into biomechanical weapons of war.

Our main character, Marcia, a former captain from Kentucky, is still recovering from the horrors she witnessed, dealt out by Athena’s creations. She is attempting to settle into her retirement, when a group of federal troops move into her small, isolated town. They need a guide through the hills, to find a weapon of Athena’s still buried in the Earth. Marcia must reckon with her home that has changed beyond her recognition, and yet still lives and breathes under her feet.

I attended the book launch event at Joseph-Beth in Lexington, where Rowe was in conversation with Ashley Blooms (another author who brings the fantastical to the South, by the way) about These Prisoning Hills. Blooms asked him about ever feeling alien for seeking genre fiction in the South, and Rowe recounted how he used to be the kid who walked the streets with his head in a comic book, sometimes feeling Othered from his community. His words hit home for me, felt like home to me, and only made me more intrigued by his book. AI taking over Tennessee? A war with biologically engineered, flying bears in Kentucky? Sign me up, if only because I so rarely found the names of my home on the back cover of a sci-fi book.

From the beginning, the nature and wilderness of the South is present, as we meet Marcia working with harvesters who are tending to the land. We read case-file snippets about the Owls of the Bluegrass, about Crow Bands who helped in the war efforts until Athena was defeated. As a child, I was fascinated by birds, owls especially. In These Prisoning Hills, I was fascinated in a whole new way, by the Owl whom Marcia meets that seems to know all, wise in the way owls are believed to be wise, with her cloak-like wings and her goggles like wide eyes. Even the members of the Crows we meet are mimicking their animal mascot, wearing headdresses, scattering, circling like raucous flocks, singing as they travel.

Why name these characters and their groups after animals? Why bring nature to the forefront of a novel that is dealing with an unknown, technologically transformed future? At his launch, Rowe discussed how he grew up with cattle and animals in general, which I once again could relate to—checking outside before letting my dog out was a common worry in my household, as coyotes were known to wander right into our backyard. A coyote would’ve loved to make a snack of my rotund little maltese-poodle mix, and their howls at night sent shivers down my spine. I worried about the scavenging animals snatching up a baby calf, but I was also curious to catch their loping form on the horizon of the hills, to listen for the hoots of owls mingling with their songs, to watch for crows circling in daylight and wonder if they found the coyotes’ leftovers.

All of that to say, in a world that is our own yet drastically changed, what is more human than to root yourself in the familiar, in the past? In These Prisoning Hills, animals are no longer what they once were. We don’t see any normal bears lumbering through the trees, or the average owl or crow sitting on a tree branch. These animals don’t exist as they once were, and perhaps, they don’t exist at all anymore. The Owls of the Bluegrass pay homage to their mascots who have become relics of the past, moving quietly like predatory birds, watching from above and guiding with the foresight of the winged. The Crows do the same, dressing in sleek black feathers, working outside of the common order but getting things done in their own way—a very crow-like way to go about life, I think. Readers may not get these animals in pure form in These Prisoning Hills, but their very spirit, and by proxy the spirit of nature, are felt through the human embodiment of keeping them stubbornly alive, despite Athena (the embodiment of human hubris and technology, if you will) doing her best to bend and warp everything to her will.

Not only are the land and the creatures within familiar, but the music as well. At his launch event, Rowe explained how music is always found in his work, and These Prisoning Hills is no exception. While the cries of crows in our world may not be defined as musical, the Crow Bands in These Prisoning Hills have marching music that they sing as they trek along. I will admit that, for the most part, lyrics on a page don’t normally do anything for me unless it’s a song I already know. I’m not skilled at coming up with a melody or sound on my own, and I tend to skim quickly through any songs that come into a story.

The song in These Prisoning Hills, however, is an exception, in that I did get to hear what it sounds like. To my delight, Rowe opened his reading by singing the entire Crow Band song, with musical accompaniment provided by his brother. It was Bluegrass music, simple and heartfelt. As Rowe stomped his foot in time to the beat, I could imagine the Crows marching in turn, their voices arcing over the hills, giving them energy to carry on. Even if I can’t suss out music without hearing it, I am an avid lover of music. I’ll listen to just about anything and enjoy it as long as it has a good beat and a tune I can carry. Sitting down and reading These Prisoning Hills, I remembered the song, and hummed along as I read, an experience I don’t think I’ve ever had with a book before. I believe that a recording of Rowe singing the Crows’ song is on the internet somewhere—I highly recommend hunting it down. It infinitely adds to your reading experience, trust me.

To speak a bit to the form, These Prisoning Hills is not a novel, but a novella, clocking in at one-hundred and thirty-eight pages. If you really have the time and the heart, you could consume this book in one reading. Taking my time and not rushing, I was able to finish this book in three days. Honestly, I recommend taking it slow, or at the very least, taking time to ruminate on this book even after it’s done. These Prisoning Hills is an exact example of quality-over-quantity. If you’re venturing into this world without any guide (AKA not having read any of Rowe’s other books in this universe, which was my situation) there will be elements that are at times confusing, at the very least befuddling, especially if you may be new to the realm of sci-fi. I encourage you to soldier on. With contemplation, it’s easy to fill in the gaps and not just accept but understand the strange world you’re in, especially if you have a prior relationship with genre fiction.

I don’t want to even come close to spoiling anything about the ending, but I will say that it ends in a way that I think it both very sci-fi and very Southern: it leaves you in the unknown. Marcia has made a decision, and the story ends before we know what consequences will come as a result of her actions, though we can hazard a guess after traveling with her throughout the novella. The ending can be read as ominous and bleak, but the relentless optimist in me reads the ending as hope. Not “jumping for joy, looking forward to the future” hope, but “tentatively creeping towards the light, hoping tomorrow will be better than today” hope. Both sentiments go hand in hand with the combination that Rowe has woven in a work of southern science-fiction.

The ending of These Prisoning Hills has so many elements perfectly intertwined, and I know it was well-done because I was left wondering what would happen but was still satisfied with what I was left with. Would I take more of this story if it was handed to me? Absolutely. Do I feel at all cheated or like I wasn’t given enough of Marcia’s story? Absolutely not. I hope that this novella provides a similar experience for you when the time comes.

If you’re a fan of: Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer, Sphere by Michael Crichton, Coil by Ren Warom, The Road by Cormac McCarthy, Salamanders of the Silk Road by Christopher Smith, or Snow Over Utopia by Rudolfo A. Serna, you’ll enjoy These Prisoning Hills. Not all those works are southern, but they all deal with transformed worlds that look like our own, as if seen through a tinted, wavering glass. By proxy, if you read These Prisoning Hills and think it’s rad like I did, you should enjoy the other works I’ve listed. I’ll also plug Ashley Blooms and her two novels, Every Bone a Prayer and Where I Can’t Follow. Her works are more so magical realism than sci-fi, but they take place in the south and feel like home. Finally, I’ll also mention that These Prisoning Hills was published by Tor.com, a publisher of all things SF and fantasy. Anything from their repertoire is a must-read.

Before I wrap-up (I promise, almost done), I wanted to touch on These Prisoning Hills from the perspective of a writer as well as a reader. Granted, I don’t have even half of the experience or publications under my belt that Rowe has, but that’s how writers learn—through the work of others.

Rowe wrote the novel from third-person past tense, which is the most popular POV and tense for most works of fantasy and sci-fi. Since present tense has a stronger sense of immediacy, past tense allows the writer to take their time with the narrative, looking back from the future, and allows for more reflection on the part of the characters. This goes hand-in-hand with the third-person POV. For first-person POV, you’re very tightly wrapped with your character, though you can also achieve this closeness with a very tight third-person. I, however, would argue that Rowe leaves some distance between readers and Marcia. We don’t necessarily get all her thoughts, each movement she makes, each emotion she feels. In this way, a writer can reveal to the audience what they need to know, and readers will inherently trust that the writer is telling you the necessities and anything beyond isn’t essential to your enjoyment of the story.

Along these same lines, the setting is well-described and alive throughout the novel. There is contrast, especially for native Kentuckians, between the green landscape we know, and the haunted hills that Marcia is exploring, her home that has become unfamiliar under her feet. Defamiliarization is one of the strongest elements a writer can use—take what a reader knows, and flip it around, shake it up just enough that we feel a sense of unease mixed with interest, and want to know more about the story we’re exploring. The setting is as much of a character in These Prisoning Hills as Marcia is.

Speaking of characters—each character in this novella is fully fleshed-out and could’ve just as easily been the main character of this story as the next. We meet Marcia’s ex-husband Carter, a man only known as the Captain, the strict and sturdy sergeant Moss, and many other characters from Marcia’s memories. There is never a sense that any of these characters exist simply to speak dialogue or fill a plot hole. Each of these characters have had their own lives, their own trauma, and their own agenda throughout the novella.

I think that Marcia, however, was the perfect protagonist for These Prisoning Hills, in that she is the most relatable character for a reader. By the time we meet Marcia, she’s an aging woman who is trying to live the rest of her tumultuous life in relative peace, only to have that all upended again by the very force that changed her life in the first place. She’s perhaps the most normal of a cast of eccentric and strong characters, and she has the most human goal of all: doing what is best for her community, and simply trying to make it home again once the situation is over and done with. Her goals may have changed by the time the novel ends— it’s hard to say for sure. But Marcia is a perfect guide, both in and out of the novel.

As far as the writing goes in general: These Prisoning Hills is a masterclass in restraint. Rowe tells an encapsulated, insular story in a world that could be explored for an entire series. If you’re hungry for more of this world, you can check out his other works, but if you only read These Prisoning Hills, you will still experience a complicated, intricate, and well-executed narrative. Basically, if you want to know how to write a novella, These Prisoning Hills is for you.

Okay, review coming to an end. Exhale now. If the previous twenty paragraphs or so haven’t made it clear, I highly recommend you read These Prisoning Hills for yourself. It has a little bit of everything for everyone—science fiction, AI, war, horror, trauma, found family, technology, bleakness, despair, and ultimately, what can be reached for as light and hope. It’s a quick read, but again, quantity has absolutely nothing to do with quality. Alix E. Harrow, author of the Fractured Fables novellas and more, blurbs that These Prisoning Hills is “haunted and heartfelt, violent and vibrant.” I will definitely be haunted by this novella, but it’s a ghost I’m welcoming for a long time.

Published on September 13, 2022